Bring the Word

“But how are they to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone toproclaim him? And how are they to proclaim him unless they are sent? As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!’” –Romans 10:14-15 (NRSV)

The word proclaim, used eight times in the book of Romans, is translated from the Greek word kerygma. Kerygma describes the teachings of Jesus Christ. The Swiss theologian Karl Barth wrote to Rudolf Bultmann that “The real life of Jesus Christ is confined to the kerygma and to faith”. Howard Thurman, the architect of the 20th century civil rights movement, understood preaching as an act of the Holy Spirit. Thurman wrote, “The movement of the Spirit of God in the hearts of [people] often calls them to act against the spirit of their times or causes them to anticipate a spirit which is yet in the making. In a moment of dedication, they are given wisdom and courage to dare a deed that challenges and to kindle a hope that inspires.” Combining these teachings, the art of preaching is not only the teaching of historical information, but proclamation is the movement of the Spirit that leads the church in to prophetic action. Jesus practiced this form of active kerygma. For example, in Luke 4, when Jesus speaks before his hometown synagogue he makes the claim that the Spirit of the Lord sent him to “proclaim [kerygma] release to the captives.”

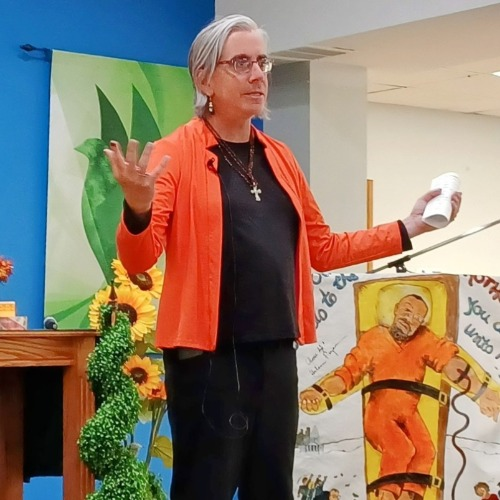

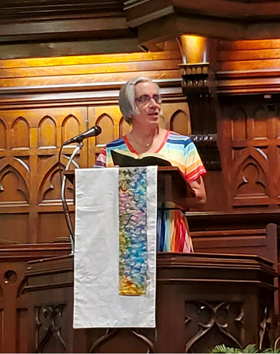

By our very presence, transgender faith leaders embody proclamation. Without saying a word, when I stand before the church on a Sunday morning as a six-foot tall transgender woman with long hair, budding breasts, adorned in jewelry and makeup, my presence communicates my divinely queer nature. Gender-diverse bodies stand as a testimony to the work of God who proclaims, “Behold, I am making all things new” and challenges the church to live in to a broader understanding of koinonia.

Every worship service at the United Methodist Church for All People in Columbus, Ohio, begins with the same call to worship:

Leader: God’s love is deep and wide.

Community: God loves all people.

Leader: Beyond differences that may divide us.

Community: No matter who we are or what we have done.

All: We are all beloved children of God

Leader: We are a church for all people.

Community: We give our love to everyone no matter who they are or what they have done.

All: Welcome to this circle.

These words are shared before every week day and Sunday morning worship as a way of claiming who we are as the beloved community, as we cabuontinue to grow in to a Church for All People. No matter who leads this refrain, these words make a powerful unifying statement that applies along line of race, class, age, and ability—God loves all of us just as we are and God is not finished with any of us yet. However, when I stand before the church, in all of my queerness, and say “Beyond difference that may divide us… We are a church for All People” the position in life from which I speak emphasizes the truth of this statement. In my gender-diverse flesh, and in the community’s acceptance of me, this statement moves from an aspiration to a realization.

Just as hormone replacement therapy changes the external physical shape of gender diverse bodies, the Spirit of God is always at work internally to make us more like Christ, known in the Wesleyan tradition as sanctifying grace. When I began taking hormones, I expected changes to my physical appearance but did not appreciate the mental, emotional, and spiritual changes that have been much more powerful. Reverend Paula Stone Williams speaks to the transformation experienced by transgender people, “You are not fundamentally the same person. You are fundamentally a different person. And you were fundamentally a different person because testosterone does not run through you any longer and estrogen does.”

Hormonal changes, coupled with the movement of the Holy Spirit, have enabled me to speak from a more authentic place. This greater authenticity equips transgender preachers to speak from experience. For example, when quoting Jesus from John 10:10, “I came that you would have life and have it abundantly,” I am now able to proclaim liberation as someone who has found life on the other side of gender dysphoria, compared to merely quoting a theological construct. Transgender preachers are particularly equipped to proclaim the transformative nature of the gospel, as we have experienced transformation within ourselves.

Vicar in a Tutu

The prophetic presence of a transgender preacher often pushes social and theological boundaries. Within the church I lead, my witness has challenged people to more broadly understand who is the neighbor that Jesus calls us to love. Even for many LGBTQ+ people, the embodiment of gender diversity by a faith leader can be difficult to hold together. Many mainline protestant denominations did not begin to ordain cisgender women until the second half of the 20th century. While many churches continue to limit the role of women to teaching children and frying chicken, the presence of a transgender preacher is an even greater challenge to gender normativity.

Millions of people have watched the TED talks of Reverend Paula Stone Williams, in which she describes how she has been treated differently as a woman than as a man. She talks “about the fact that life’s much more difficult for women than it is for men” and that as a preacher “the difference in how the audience receives the information.” For Williams, the questioning of her authority as a woman has caused her to gain a greater sense of humility, coupled with the confidence she was raised with as a person assigned male at birth. Williams’ personal reflection illustrates that transgender preachers are not only transformed by their own internal changes, but in how they are received by the world.

Bumping up against cultural unexpectedness can leave the transgender preacher feeling pressured to take one of two approaches to preaching: one of defensiveness in deconstructing what have become known as the “clobber passages” used to condemn queer people; or, one of validation pointing to times that scripture lifts up and centers gender diverse people. Multiple books and online resources exist to address the clobber passages. Similarly, scriptures that center on eunuchs (Isaiah 56:5, Matthew 19:12, Acts 8:26-40) offer more scriptural support for gender than sexual diversity.

While transgender people have unique life experiences that lead to a prophetic proclamation around issues of gender and sexuality, we are not single-issue preachers. A richer transgender hermeneutic brings a wide range of gender-diverse experiences and perspectives to the full body of kerygma. In practice, the transgender voice offers fresh perspectives on the full breath of topics such as grace, salvation, sin, ecclesiology, missions, and justice.

Exquisite Exegesis

The Franciscan priest, Fr. Richard Rohr, offers a perspective of Biblical interpretation, “How Jesus Used Scripture.” Rohr describes Jesus’ hermeneutic: “He never quotes the book of Numbers, for example, which is rather ritualistic and legalistic. He never quotes Joshua or Judges, which are full of sanctified violence. Basically, Jesus doesn’t quote from his own Scriptures when they are punitive, imperialistic, classist, or exclusionary. In fact, he teaches the exact opposite in every case.”

To claim that Jesus taught through a hermeneutical lens of love is not to say he didn’t challenge the status quo. Jesus held together speaking in love with speaking truth to power. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.”

Jesus held together power and love as he broke cultural gender stereotypes when he sat and talked with the woman at the well (John 4) and called on women to preach the first resurrection message (Matthew 28). Jesus instructed the disciples to look for a man carrying water who would lead them to the Upper Room (Mark 14:13-15). This violation of cultural norms has led Bible commentators to wonder if the water carrier is a trans-cestor.

Many transgender people take voice lessons to learn how to speak with an audible voice more authentic to their gender expression. Just as a different voice pitch can move a person from gender dysphoria to euphoria, a deliberative transgender theology provides space to preach from a unique and authentic gender-diverse perspective. While the aforementioned clobber passages have been used to shame and exclude, a hermeneutic of love can offer a vision of sacred value and inclusion.

As previously mentioned, gender transformation results in internal and external changes within preachers. For many preachers, this results in a change in social location. When I came out as a transgender woman, a friend asked me why I would give up the privilege of being a white cisgender male. While I had to transition for my own well-being, it led to the development of a new hermeneutic. I began to read scripture from the perspective of the marginalized and preach from that vantage point. For example, the story of Pentecost is not only one of disciples speaking in different languages but of people being able to hear the good news in their own context, “because each one heard them speaking in the native language of each.” As a pastor who has heard the good news in her own queer context, I am then able to challenge the church:

How can we speak in a way that would lead other people to look at us and say “how is it that we hear, each of us, in our own native language?” Historic South Siders, International immigrants, people who live off the land, people who own the land, Buckeyes, Bobcats, Republicans, Democrats, Socialists, Communists, Vegans, Atheists, Anglicans, Appalachians, African-Americans, Asians…

I Hear My Voice

CatholicTrans blogger, Anna Magdalena Patti, writes:

Coming out gives queer Christians the chance to witness to the real power of Christ in our lives, not the fake ‘ex-gay’ sort of forced testimony… We can talk about God’s love for us, about the spiritual lessons our unique life experiences have taught us. We can talk about how we continue to grow, how we continue to struggle to be joyful witnesses of the Gospel, how we are broken people to whom God gives the daily grace to survive. In short, we can actually preach the Good News, not the Socially Acceptable News.

Transgender people are particularly equipped to preach about the transformative power of love because of their transitional experiences. I have experienced this myself as I am now able to preach as much from the heart as from the head. Today, I often find myself preaching with eyes closed as I am speaking from the core of my being. Reverend Paula Stone Williams shares her experience of preaching with greater authenticity as a transgender woman, “Now I preach with more nuance; I speak more confessionally and more transparently. I sit with the text and listen for the whisper of God, filtered by my experience and the imagined experience of my listener.”

Playright Jo Clifford embodies the example of a transgender performer who has experienced gender transition that has shaped who she is; and, has been received by audiences with strong responses—positive and negative. Clifford’s first play, “God’s New Frock,” tells of her experience not fitting in as a “boy” within a religious boarding school system and how her own mis-assigned identity is connected with misunderstanding the masculine nature of God. Clifford notes how God “suppressed her own feminine self just as I had to do when I was young.” In the play, she writes:

And maybe like me when you were first told it you were very little

And you were told it was the story of God

Who was very big

And what he did when he made the world.

And that means it’s also a story about me. About me and about you when we were all boys or maybe girls

In her next play, “The Gospel According to Jesus, Queen of Heaven,” Clifford built on the international attention of the first. Like many authors who have placed Jesus amongst the oppressed, Clifford tells the story of Jesus coming back to earth as a transgender woman. The play received strong responses, both as a rallying call for LGBT+ people and condemnation from religious authorities. The Archbishop of Glasgow said it was hard to imagine a greater affront to the Christian faith than her play. In Brazil, the act of showing up to attend the play became civil disobedience for queer people, while at the same time Clifford and performers received death threats. The play begins with Clifford depicting a feminine Jesus who says

I never said: Beware the homosexual and the transgender and the queer because our lives are unnatural or because we are depraved in our desires… Because I, Jesus of Navareth was and am one of them. I was always queer. I always am queer and I always shall be queer from now until the end of time! And that’s the sermon over.

Clifford’s proclamation connects with the arc of prophets across time. In a February 2024 sermon titled “How to be a Prophet,” Clifford compares her own journey, and by effect the journey of transgender preachers, with Elijah and Elisha:

And I know we’re none of Old Testament prophets here today – at least I don’t think we are – but we go through a very similar kind of process ourselves.

As we try to discover who we are and what we are going to do with our lives.

There’s a conscious element to all this: a decision that may involve us in a whole load of hard work as we train to join our chosen profession.

But at the same time there’s something mysterious about it.

Something going on we don’t fully understand.

And sometimes those we love don’t like it.

Sometimes we don’t like it ourselves.