THIS IS AMERICA

In 2019, 32 anti-transgender bills were proposed across the United States. In the first six months of 2024, 619 anti-transgender bill were under consideration in 43 states. Another 61 bills were introduced at the federal level. This marked the highest amount of anti-transgender legislation in any year—a record broken in only six months. Not only has the number of bills exponentially increased over the last five years, the legislation targets basic human rights such as healthcare, education, legal recognition, and the right to exist.

The increase in anti-transgender bills spiked after the 2022 Supreme Court Dobbs decision that overturned abortion rights granted under Roe v Wade. Organizations who spent decades, and hundreds of millions of dollars, seeking to exercise control over reproductive rights redirected their energy, funding, and tactics toward transgender bodies. For example, Kristen Waggoner, President of the right-wing Alliance Defending Freedom, stated that after winning Dobbs their organizations next priority was taking on “the radical gender-identity ideology infiltrating the law.” Waggoner said that she does not believe in transgender identity but that people are made uncomfortable in their bodies because of a “social contagion.” These views are being put in to law as the Alliance Defending Freedom has developed from an outgrowth of Focus on the Family to a network of over 4,900 lawyers, fueled by an annual budget of over $100 million a year, drafting state laws.

One example of the type of legislation supported by the Alliance Defending Freedom is Ohio House Bill 68, “Enact Ohio Saving Adolescents from Experimentation (SAFE) Act”. While the title of this bill claimed to protect minors from “experimentation,” it actually removed the ability of medical professionals to provide evidence-based gender-affirming care, despite clinical diagnosis, parental consent, or individual impact. This ban prohibits physician services, inpatient and outpatient hospital services, and prescription drug hormones to transgender youth.

On April 19, 2023, Representative Gary Glick proposed House Bill 68 to the Public Health Policy of the Ohio legislature. During the hearing, a member of the health committee asked Click, a Baptist pastor, if he had the expertise to disagree with the endorsement of the American Medical Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and a long list of other professional medical groups that supports gender affirming care. Click responded that these groups represent the interest of a few, liberal elites and results in harm perpetrated against minors.

In the same testimony, Click went on to describe the number of transgender youth who attempt suicide as exaggerated. He accused the Trevor Project of inflating numbers to validate their arguments. According to a study published by the National Institute of Health, 82% of transgender people have considered killing themselves and 40% have attempted suicide, with suicidality highest among transgender youth A study published by the Journal of the American Medical Association noted that access to gender-affirming care reduces rates of depression and suicidality. Access to healthcare “was associated with 60% lower odds of moderate or severe depression and 73% lower odds of suicidality over a 12-month follow-up.”

Despite scientific evidence endorsing transgender healthcare, the Ohio legislature moved forward with its legislation. On December 10, 2023, the legislature received more than 600 pieces of written opposition testimony and heard eight hours of in-person testimony from doctors, healthcare providers, parents, and transgender youth. Nick Lashutka, president and CEO of the Ohio Children’s Hospital Association testified, “HB 68 uses false information to strip away parents’ rights and impose non-scientific restrictions on pediatric healthcare specialists. It bans all healthcare and medications that are used in extremely limited but critical circumstances. It is a dangerous precedent for government to dictate when medication is appropriate in pediatrics.”

Neither medical/scientific evidence nor the pleas of youth and parents impacted legislators. Not only did the Ohio State Senate pass the bill on December 13, 2023, but had enough votes to override the veto of Governor Mike DeWine in January 2024. House Bill 68 became effective law in Ohio on April 24, 2024. Not one republican senator voted against party lines to override the governor’s veto. Countless hours of traditional advocacy: calling, visiting, testifying and writing legislators did not impact change. State Senator Catherine Ingram responded to the veto override, “All Ohioans deserve access to the health care and support they need, care that does not include the opinions and fear-mongering of politicians. It is a dreadful time in our state where LGBTQ+ Ohioans do not feel safe.”

TAKE THE POWER BACK

Another approach to justice work is to move from reactive to proactive advocacy. Instead of only responding to negative legislation, working to create a more inclusive world through protective legislation. For transgender people, as well as other marginalized groups, these laws typically center on anti-discrimination laws that provide legal protections for things like education, employment, and housing. Additionally, hate-crime laws seek to make gender identity and expression a protective class.

While laws such as these offer legal standing, recognition, and protection for gender diversity, they have not resulted in creating equity. Anti-discrimination laws do not reduce discrimination; hate crime laws do not reduce violence. These laws make important statements, but have not resulted in increased access to jobs or housing; and, have not created safer communities. Lawyer and trans activist Dean Spade writes “Hate-crime laws do not have a deterrent effect. They focus on punishment and cannot be argued to actually prevent bias-motivated violence… Antidiscrimination laws are not adequately enforced. Most people who experience discrimination cannot afford to access legal help, so their experiences never make it to court.”

Just as reactive legislation has not prevented restrictive legislation, proactive legislation has not improved the well-being of transgender people. Sociologist Rayna E. Momen writes, “Reversing these trends requires everything from changes in laws and culture, including a belief that trans people deserve equal rights, to a commitment to change at the individual and structural levels. It necessitates attending to intersectionality in order to meet the needs of all trans people, rather than a select few.”

INTERSECTIONALITY

The key to developing a more effective methodology of justice is through a lived practice of intersectionality. Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw coined the term in 1989, specifically to describe how race and gender interact to shape the experience of Black women. Since coining the term, Crenshaw has gone on to develop the concept and explore “various ways in which race and gender intersect in shaping structural and political aspects of violence against women of color.”

While Crenshaw developed this concept to describe the identities and discriminations faced by Black women, intersectionality has come to describe the multiple parts that shape many people. An awareness of intersectionality forces marginalized groups to look beyond themselves. For the LGBTQ+ community, this means looking beyond issues of queer inclusion alone and seeing a shared interdependence on issues like immigration, prison reform, and the environment. Often, groups operate within what is perceived as their own self-interest; and, from a scarcity mindset believe that spending resources and social capital on another issue does not help their own. Intersectionality challenges that notion and recognizes the background of shared oppressions and vision of shared liberations. Anthropologist Elijah Adiv Edelman writes:

I would prefer we see ourselves not as one community but as coalitions struggling in tandem with one another. Through viewing ourselves as working through coalitional efforts, we can begin to name the ways we are linked in complicated and hierarchal ways that may then undergird a logic of visualizing social justice as necessarily messy and disruptive across planes of need, identity, and politics. It is through this recognition of complex and unequal life, the humanization of the other, and even of the political enemy, that we can shift away from a reliance on exploitation, exceptional amnesia, and oppression toward movements that create livable realities for all.

Intersectionality is not limited to issues of race and queerness, but incorporates all issues of privilege and marginalization. For example, during Pacific School of Religion’s 2024 Pride Celebration, student Jessie Jay Ratcliff talked about the impact of climate change on transgender people of color who experience “limited access to green spaces, increased vulnerability to climate change, and pollution from industrial facilities.” Ratcliff challenged participants, “In the fight for environmental justice, we must recognize that the liberation of trans people of color is inherently intertwined with the protection of our planet. Our struggles are interconnected, and our collective resistance holds the power to create a more equitable and sustainable future for all.”

Awareness of intersectionality serve as a challenge to the LGBT+ community. Historically, queer leadership and advocacy have come from a predominately white, privileged homonormativity which has often assimilated to heteronormative expectations. From this, expressions of what it means to be a “safe gay” stand in contrast to the diversity of the broader queer community, resulting in silencing the voices of those most vulnerable. As such, working from a place of intersectionality is liberative for the queer community itself, in order to address its own issues of poverty, homelessness, violence, and mental health issues. The faces shown every year during Transgender Day of Remembrance are not those of “safe gays” but of young, Black, transgender women. Our own liberation as a queer community is interdependent on operating through a practice of intersectionality. Toronto Activist, Syrus Marcus Ware, shared their vision at a roundtable conversation:

I’m thinking about the microcosms of organizing in the city, including independent networks of people doing community accountability, in trying to deal with conflict in their communities, and people organizing around social change, whether through groups like the Black queer and trans arts/activist collective Blackness Yes! or the migration/border activist movement No One Is Illegal. I’m also just thinking about the possibilities.

QUEERING JUSTICE WORK

Advocacy around transgender rights often looks like traditional justice work, using the “inside game” of contacting elected representatives and submitting testimony. However, with the transgender population making up roughly one percent of the general population, the amount of impact that the inside voice can have on its own is limited. Effective justice work includes the “outside game” of community organizing, rallies, and bringing external pressure.

While traditional justice work employs this inside/outside strategy, queering advocacy results in a much greater emphasis on the outside game–organizing intersectional coalitions to the point of shifting centers of power. Historically, systems of power have worked to separate marginalized peoples from each other, such as pitting poor white people against poor Black people and blaming immigrants for lost job opportunities that are the result of corporate greed. A queer perspective would be to flip this division and build coalitions in which the combined force of oppressed communities becomes the power that forces change.

The process of queering justice work and living in intersectional coalitions begins by recognizing shared oppression. Marginalized groups share in common the effects of being on the outside of systems of power such as capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, racism, and colonialism. Audre Lorde wrote in “There is No Hierarchy of Oppressions”:

I cannot afford the luxury of fighting one form of oppression only. I cannot afford to believe that freedom from intolerance is the right of only one particular group. And I cannot afford to choose between the fronts upon which I must battle these forces of discrimination, wherever they appear to destroy me. And when they appear to destroy me, it will not be long before they appear to destroy you.

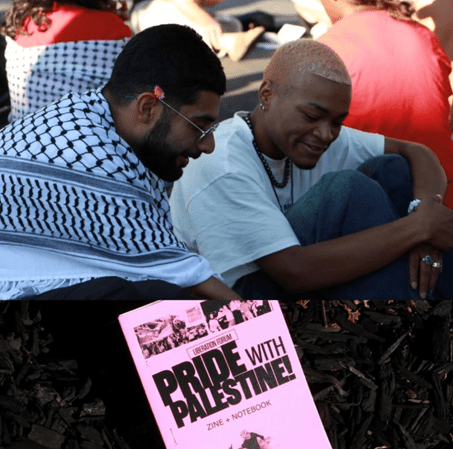

On June 27, 2024, a group of two dozen queer justice leaders gathered in Columbus, Ohio for a forum, “Pride with Palestine.” Participants of the gathering, scheduled to take place in a downtown public library, were greeted by police tape and a closed front door. The Columbus Police used a stabbing outside the library to pressure the librarian to close the building. In previous months, tensions ran high between Ohio State University students protesting for a ceasefire and Columbus police.

Undeterred, the group moved outside to the parking lot and met for two hours building awareness between LGBTQ+ and Palestinian justice. The group talked about the history of systems of power separating marginalized groups. This manifest itself in queer movements to build solidarity with Palestine. While queer and Palestinian peoples have both suffered oppression because of the forces of colonialism, Israel has used tactics of “pink-washing” and “rainbow washing” to attempt to drive a wedge between the two. This messaging attempts to portray Israel as progressive and inclusive of queer people, as illustrated by pride celebrations in Tel Aviv, while Israeli law prohibits same-sex marriages.

In 2024, college campuses across the United States erupted with protests calling for Palestinian ceasefire. At the same time, the practice of pink-washing was used to try and deny the existence of queer Palestinians; and, moreover, to block the reality of shared marginalization and freedom for Palestinian and LGBTQ+ peoples. This gathering in Columbus, which local police tried to thwart, concluded with this statement:

All working and oppressed people here in the US, including LGBTQ+ people, should unite in support of Palestinian liberation. We share a common enemy: the LGBTQ-phobic, racist, imperialist US government and the proxy states it uses to police the globe on its behalf, including Israel. When it is gone, and we can build a new world with respect for the self-determination of all people, then we will be free.

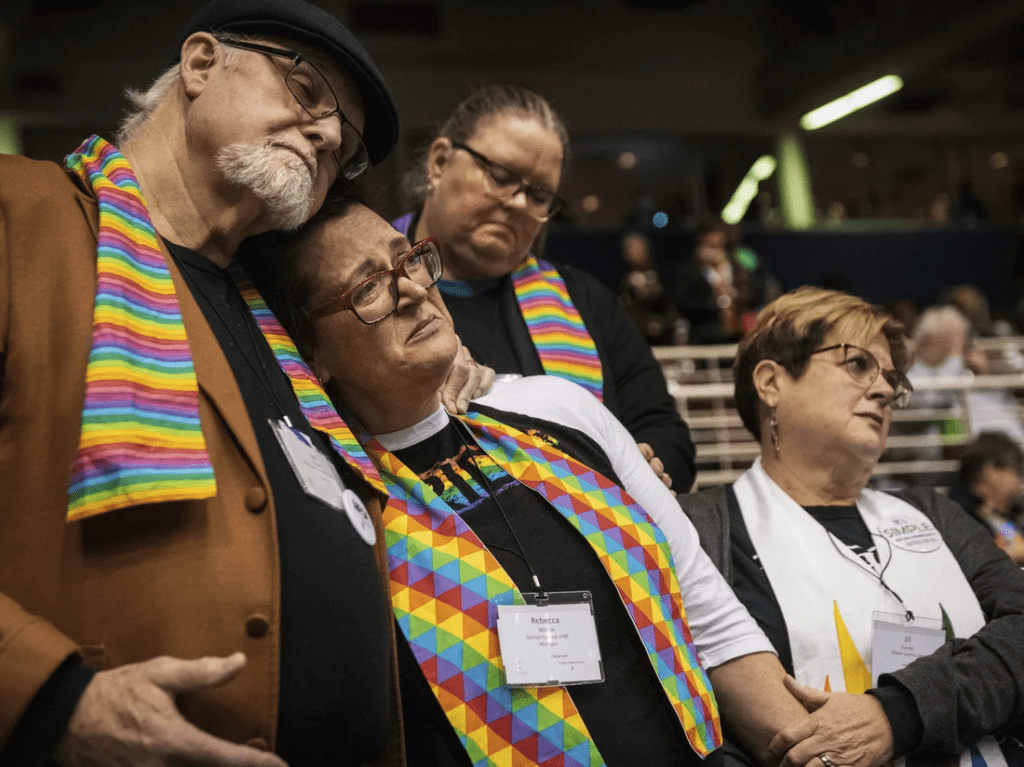

An example of effective intersectional justice work happened at the United Methodist Church’s General Conference that took place in May 2024 and lifted restrictions on LGBTQ+ clergy and allowed for same sex weddings. Reforms were so overwhelmingly supported that they passed by margins of 92 percent on omnibus consent calendars.

These historic changes did not happen as a result of “hopes and prayers” alone, but after decades of relationship building and organizing. The 2014 Supreme Court Obergefell v Hodges decision forced states to issue marriage licenses to same sex couples and to recognize same sex unions. While marriage equality became the law of the land, it was not permitted within the United Methodist Church. Historically the church positioned itself as the practiconer of weddings, but now found itself outside the ability to perform them for many people.

With the confluence of history pushing against it, the United Methodist Church called a special General Conference in 2019 to resolve issues around human sexuality in the church. Instead of becoming a more inclusive church, the conference ended with the passing of the “Traditional Plan” that maintained restrictions against queer clergy. As the final votes were being taken, LGBTQ+ observers were locked out of the conference hall and the sound of fists pounding on doors and desperate cries for justice echoed through the conference center.

Initially, it seemed that “traditionalists” had taken the United Methodist Church. However, the more restrictive legislation and actions taken to achieve it created a backlash. This backlash provided space for coalitions to be built between centrists and progressives and international delegations. Bishop Karen Oliveto, the first openly lesbian bishop in United Methodism wrote, “This is why the decision at General Conference is creating such backlash and dissent—it is no longer a Progressive-Traditionalist disagreement about the role of LGBTQ people in the life and ministry of the church. It is a struggle for the very ethos of Methodism itself that crosses the theological spectrum found in our church.” With a growing, diverse organization supporting inclusion, and delays caused by the coronavirus, conservatives formed their own denomination, the Global Methodist Church. Roughly one-third of United Methodist congregations disaffiliated and joined the Global Methodist Church.

One example of the intersectional work that built a more inclusive church happened on May 2, 2024, as General Conference debated the definition of marriage. Molly Mwayera, a delegate from the Zimbabwe East Conference, rose to offer an amendment to define marriage. Mwayera did not precisely follow Roberts Rules of Order and spoke with a thick accent. However, instead of being dismissed, the presiding bishop and conference body worked with her. Mwayera crafted the language that recognized marriage as between a man and a woman or between two adults. The United Methodist Church’s official definition of marriage came from a Zimbabwean woman.

Looking through the eyes of intersectionality demonstrate the potential of what can happen through organizing and relationships. Effective queer justice work cannot succeed by bringing reforms through tradition systems of hierarchical power, but requires building relationships amongst intersectional marginalized communities. As Audre Lorde writes, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”